This week, a look at the relationship between teaching with primary sources and civic empowerment in students; an examination of iEngage, a summer civics camp, and its implications for the effect of action civics on the civic competence of students; a study of how civic engagement in early adolescence lays the developmental groundwork for involved citizenship in adulthood; a counterpoint to the prevailing narrative that young people don’t vote through a study of youth political activism in California’s Central Valley; and finally, a look at how the changing digital culture of young people is being increasingly employed for civic organizing and empowerment.

Organizing as an Intellectual Tradition

Out of the Archives and Into the Streets: Teaching with Primary Sources to Cultivate Civic Engagement: Jen Hoyer

In the United States today, there exists a civic empowerment gap between non-white, immigrant, and low-income youth and their white, middle and upper class peers, stemming from systemic inequalities in education and civics teaching. It is most clearly manifested in their knowledge of history, politics, local issues, and current events; skills to analyze and communicate this knowledge; and the agency to make tangible changes to the status quo by taking civic action based on it. Students and families who live in socioeconomically disadvantaged neighborhoods have fewer opportunities to access this knowledge, and fewer opportunities to apply it through active civic engagement, resulting in attitudes towards civic participation having a disproportionate correlation with socioeconomic status and race. This gap exacerbates the larger opportunity gap which already exists between these groups: individuals who become civically engaged as young people are provided with more access to scholarships, internship opportunities, and jobs. Student activism also cultivates essential soft skills such as leadership skills, communication strategies, the ability to consider multiple viewpoints, and critical thinking. Teaching with primary sources within the framework of civic empowerment (instead of restricting it to history) can provide students with the higher order thinking skills needed to participate as democratic citizens, and give them the agency they need to take action by connecting their struggles with a historical tradition of organizing. For example, programs at the University of Kentucky and University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign that used primary sources documenting past civic engagement on campus helped develop students’ sense of their potential as actors of change within a larger historical tradition of civil disobedience.

To fully understand the potential of primary source teaching to close the civic empowerment gap in disadvantaged communities, Hoyer utilizes a case study of the Brooklyn Connections educational outreach program at the Brooklyn Library archives. In the program, a Brooklyn Connections educator teaches students how to do research with primary sources, with primary source documents being centered in every lesson and at least one site visit to the Brooklyn Library archives for in-person research. Students then use these skills to research a Brooklyn history topic. While the program does not specify that students’ final projects take the form of civic engagement, an increasing number of partner schools with student populations that fall demographically within the civic engagement gap have used the program to do so. At East New York Family Academy, a school where 82% of students qualify for free or reduced lunch and where 95% of students are black or hispanic, teachers chose to have students research local neighborhood history to challenge current public perceptions of the neighborhood as dirty, poor, and dangerous, resulting in the compilation of a timeline that depicted its rich history. At City Polytechnic High School, where 72% of students qualify for free or reduced lunch and 88% are black or hispanic, students researched the history of Brownsville in order to design a neighborhood community development plan— complete with a scale model— that was presented at a Community Board meeting. At the Urban Assembly school, students used their research in a series of community outreach activities in response to an increase in hate crimes in their neighborhood; this resulted in them speaking at an anti-hate rally and being interviewed on local radio and television. An informal analysis of these outcomes finds that when combined with community issues that allow students to connect their own lives to what they are studying, primary source teaching not only allows students to build thorough content knowledge (as they did in all instances) and higher order thinking, research, and communication skills, but also learn how to effectively apply their learning to enact social change.

Effective Civic Learning Through Authentic Civic Activities

Developing Civic Competence Through Action Civics: A Longitudinal Look at the Data: Karon LeCompte, Brooke Blevins, Tiffani Riggers-Piehl

LeCompte and colleagues’ paper centers on student outcomes from participating in a week long out of school action civics program intended to increase students’ civic competence and engagement. Action civics is an educational practice consisting of curricula and programs which go beyond the passive learning about government and civil rights present in most traditional civics education courses. This approach is purposefully political and policy-oriented, pushing students to act and behave as active citizens by engaging them in a cycle of research, action, and reflection about issues they care about while learning about deeper principles of effective civic and political action. There are six stages in any action civics program: examining the community, choosing issues, researching an issue and setting an achievable goal, analyzing the power structures affecting that issue, developing strategies to tackle it, and taking action to affect policy. These steps actively involve students in the political process by helping them take ownership of a civic challenge they care about while also supporting the acquisition of knowledge necessary to create change. In 2013, the authors developed and implemented a free, weeklong summer civics institute for 5th-9th graders called iEngage which utilized the action civics model to foster participants’ understanding of and engagement in political life. Through qualitative and quantitative data collected throughout the course of the program, the authors seek to answer two research questions: how did students’ civic competence change as a result of their participation, and how was students’ experience connected with their levels of civic participation post-program?

The results of the program demonstrated a significant improvement for about half of the civic competency variables the study tracked. For example, following camp participation, students recorded higher scores in their ability to organize a meeting, express their views in front of a group, write an opinion to a local newspaper, and contact an elected official. There was a difference in the effect of the program on first-time participants compared to repeat participants: first time participants indicated significant gains in these areas, while repeat participants reported gains which were not statistically significant. The increases were consistent across different ethnic and gender groups participating in the program. These gains were a result of the program involving students in the political process through authentic civic activities; for example, students were able to interact with local civic leaders and ask questions about public policy as part of the process of developing their advocacy projects. What this data suggests is that action-oriented, project-based civics education, which moves beyond the confines of voting and traditional civic participation, empowers students to imagine themselves as civic actors and, as a result, correlates with stronger civic competence outcomes.

Early Signs of a Citizenship Development

Patterns of Civic and Political Commitment in Early Adolescence: M. Loreto Martinez, Patricio Cumsille, Ignacio Loyola, Juan Carlos Castillo

Early adolescence is a particularly relevant period to track the civic development of young people because it is the period in which profiles of civic interest and involvement first start to emerge, and where the search for expanded autonomy leads to commitments being developed beyond the family. Investigating the opportunities that young adolescents have to exercise participation rights can shed light on how schools and communities can enrich the initial civic development of young people; however, knowledge of how these dispositions and attitudes emerge is limited. Martinez and colleagues use Chilean youth as a case study to study the emergence of civic attitudes, acknowledging that previous scholarship on this process was centered on youth in the United States. The researchers analyzed involvement in civic organizations during early adolescence, and hypothesized that general disillusionment with formal politics would translate to low rates of engagement in political organizations but high participation in organizations that pursue social and community service projects. As a result, the three objectives of the study were to identify patterns of civic engagement in a large sample of young adolescents, examine whether these patterns differed by gender and socioeconomic status, examining the influence of family and school in predicting these patterns of engagement.

In their results, the researchers outlined 4 major classes. Class 1, uninvolved, was the most prevalent at 44% of the total sample; however, because this percentage was defined as a lack of participation in the specific organizations listed, it does not necessarily indicate that this percentage of the population was completely disengaged. Class 2, volunteer, represented 27% of the total group, and accounted for those participating in community organizing and religious organizations. Class 3, random, represented 29% of the sample and accounted for those who had circumstantial reasons for community participation (such as an academic requirement). Class 4, involved, was the least represented at 7.4% of the sample, representing those with a high probability of participating in one of the community organizations assessed. These findings contributed to the existing knowledge in three main ways. First, it confirmed that there are distinctive patterns of civic participation in young adolescents in a different population than initially assessed. Second, it documented the heterogeneity in civic engagement patterns according to gender and socioeconomic status; women were overrepresented in the volunteer and involved classes, while men were overrepresented in the uninvolved class, and participants with high SES were more likely to be in the volunteer class than their lower SES peers, who were more likely to be in the random class. Third, it highlighted specific family and school experiences that predict membership in different forms of participation. Specifically, regardless of SES, school emerges as a key context where students can be engaged in quality participation experiences through extracurricular activities through which they begin to realize that their voice matters, and begin to have input on important decisions which affect them. These trends can help pinpoint where civic education and intervention are necessary, and where young people may begin to slip through the cracks.

Citizens of the Future

Youth Led Civic Engagement and the Growing Electorate: Findings from the Central Valley Freedom Summer Participatory Action Research Project: Dr. Veronica Terriquez, Randy Villegas, and Roxanna Villalobos

Between the 2014 and 2018 midterm elections, the number of adults aged 18-24 who voted in California’s primarily rural Central Valley jumped from 32,414 to 85,007, a surprising 262% increase. The reason for this dramatic increase goes beyond the polarizing national political climate: inspired by the 1964 Freedom Summer effort, youth members of community based organizations played a central role in mobilizing voters through the Central Valley Freedom Summer Participatory Action Research Project. The importance of this project stems from the long history of ethnic tension in the Central Valley, often referred to as California’s “Deep South.” White political power in the region was consolidated after a mass deportation of Mexicans and Filipinos in the 1930s due to racial conflict in the agricultural labor force; the resulting labor shortage was filled by Whites who migrated to California to flee the Dust Bowl, and brought with them conservative politics fueled by racism and cemented through KKK violence throughout the region. Today, this conservative culture and racial tension remains, resulting in the suppression of its large Latinx communities through both overt means, such as police violence, and covert ones, such as excluding important Latinx organizers such as Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta from history curriculums. Though Latinx immigrants and their descendants outnumber the White population, the White population is still able to wield a disproportionate amount of political power because of low rates of registration and voting among the Latinx community.

The CVFS project sought to address these inequalities by building the political power of the young Latinx population through voter education. Students partnered with community organizations such as 99Rootz and Californians for Justice who provided them with guidance in navigating the political landscape, as well as providing additional training, meeting spaces, and supplies to further their efforts. Local organizations also served as an infrastructure that could engage newly politically active youth beyond a single summer. As well as supporting organizations’ existing campaigns, students conducted voter registration and education, planned local conferences, and conducted broader outreach on the importance of voting through art activism and media outreach. By tapping into family and community networks, CVFS students were able to create local teams that were responsible for carrying out voter registration drives and other outreach activities. These horizontal organizing structures were invaluable to the project and contributed to the initial registering or pre-registering of over 4,000 new voters, as well as the continuing momentum of the project culminating in the 262% increase in voter participation after CVFS concluded. The most effective forms of outreach included daylong conferences featuring student-led workshops which sought to address the disconnect between what students learned in school and how civics is actually practiced, and art activism such as creative work amplified through social media and public murals celebrating minority culture and political power. However, the project also revealed challenges in political organizing in semi-rural and other communities without a history of student activism. For example, young residents were at times skeptical of CVFS leader’s claims that they could contribute to changes in their communities, and some school administrators initially blocked students from conducting voter registration on high school grounds even though it was legal under California state law. However, by building alliances with supportive school board officials and community leaders, students were able to overcome these challenges and even contribute to permanent policy change in which schools committed to conducting outreach efforts after CVFS concluded through programs such as distributing voter registration cards to all students and creating a dedicated “Outreach Month.” These broad school and community based alliances spurred the dramatic increase in voter turnout in the Central Valley region and strengthened Latinx community power; they serve as an example for future efforts at similar community organizing.

Harnessing Digital Culture for Social Good

The Civic Potential of Memes and Hashtags in the Lives of Young People: Paul Mihailidis

The unprecedented ways that political information is exchanged today, and the amount of democratic input present in platforms for sharing such information, has resulted in an evolution in the way young people organize and engage in politics. Memes and hashtags have emerged as key delivery tools for political expression in digital culture. Mihailidis cites Shifman’s articulation of the three main purposes that memes serve in these spaces: (1) a vessel for cultural information to pass from person to person, but gradually scale into a shared social phenomenon, (2) reproduction of a shared idea through means of imitation (numerous variations of the same meme), and (3) the diffusion of ideas through competition and selection in large-scale social networks. Hashtags serve a similar function in disseminating information in a horizontal fashion. Research has shown that hashtags are used as reliable curators of information, online conveners for social movements, and mechanisms to support aid networks for protests and campaigns based on virality.

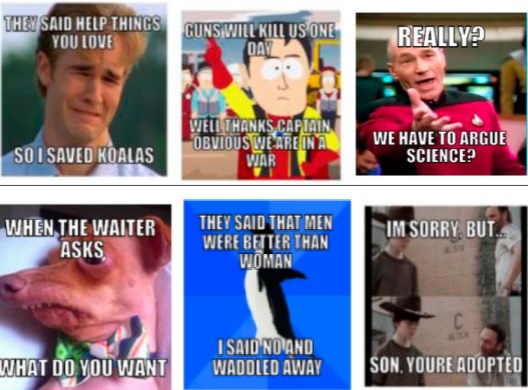

Mihailidis’s paper seeks to explore the attitudes of young people towards memes and hashtags as tools for meaningful civic and political expression. The design of the study employed a digital literacy intervention, part of the Emerging Citizens online digital toolkit, for 93 young people ages 13-16 in four public schools in the Greater Boston area in order to gauge their attitudes toward online platforms for civic engagement. The two tools used in the study were Hashtag You’re It and Meme Machine. The former is designed for creative hashtag creation, in which users are exposed to real tweets about relevant social and civic issues, and were asked to come up with a hashtag to fit the tweet. The latter asks students to create memes based on civic prompts, such as gun control and climate change.

Because the experiment was designed as an exploratory investigation into student attitudes, controls and quantitative measurements were not included in the study. However, from coding and refining the qualitative data collected from debriefs after the students went through the experience, researchers were able to pinpoint three overarching trends: negativity, playful resistance, and reluctant engagement. In the first group, students articulated reluctant and negative responses to social media in general, citing a greater awareness of how these platforms can be commodified. They mentioned fake news and the activities of President Trump as reasons to distrust these sites, and expressed skepticism on the political relevance of memes and hashtags. In the second, students primarily employed humor and sarcasm to point out social injustices and flaws in the current system, relying on their day to day knowledge of current events to do so. In the third, students’ replies indicated that they were not ready to declare these techniques valuable catalysts for social change; they saw the advantages of using these forms of communication to spread information and engaging messages, but saw their potential for use as limited because they exist in social networks. Overall, these results demonstrate that there is a potential to nudge perceptions of the value of technology for civic engagement, and a need to develop more digital avenues for young people to embrace communication technologies for civic purposes; these modes of communication have the potential to build robust civic cultures among this demographic, a crucial prerequisite to political action, and as a result future quantitative studies are worth pursuing.

Examples of memes created by group 2 pictured below.

Written by U4SC Summer Intern, Julia Pepper